Old Friends – Returning to Tokyo

Tokyo. Wake up. 8:30 AM.

Got in the night before, delayed flight. Got Yen. Crashed at 3AM.

Shower. Breakfast. Out the door.

The mission:

Visit old friends: Places I’ve been missing since 1999, when I left here. Two of my favorite restaurants in the world. Akihabara Denkimachi (Lightning-Town). Find an otaku shop: See if I can connect with Tokyo board-game culture. Visit the Kinokunia bookstore: See if the toilets there are still lit up with more glowing controls than a science fiction set.

First stop: Akihabara. Not finding the electronics parts stores of old, where folks would stand over racks and racks of specialized components. Did I miss the right turn off the main street, or has that moved to Huachangbei in Shenzhen?

Well, here’s an arcade, let’s get a game in at a sit-down machine.

Nerd stores: Well, this is awesome. Look at all these mecha kits. Look at all these random parts in baggies, so you can kit-bash your mecha.

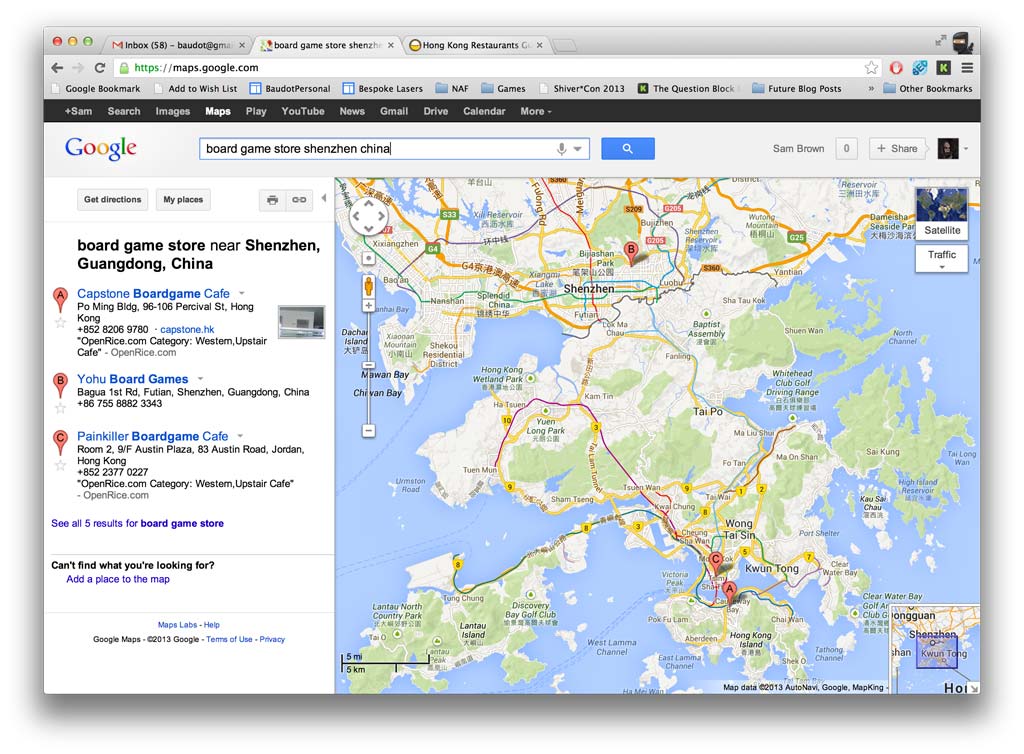

Mission: Find boardgames in Tokyo: Failed.

Lunch: Find my favorite old soba stand. That was 14 years ago. The guy who ran it was old. Can it still be there? It was at the corner of a tiny alley out of an exit from a train station that defies the laws of geometry.

Yes, my feet still know the way.

(2021 Update: Apparently the alley is named “Omoide Yokocho”!)

Found the right exit from Shinjuku station, found the right alley… my feet still know the way. It should be ahead, on the left…

It’s still there. Two young guys are running it tonight.

It’s just like I remember. The best soba in the world. 380 yen for a bowl, tempura and an egg on top.

24 Hours to Beijing; Standing Room Only

Shenzhen is at the southern edge of China. If you went any further south, you’d fall in the water. And then a short swim later, you’d be at Hong Kong.

Beijing is in the north. It’s in the name, even. Bei Jing: North Capital. Nanjing, better known as Nanking, is literally “South Capital”. “East Capital” was already used by another city, so China didn’t get that one: DongJing. The locals pronounce those same characters ToKyo instead of DongJing. If there’s a XiJing, a West Capital, I haven’t yet heard of it.

So:

From south, as south as China gets to North, most of the way to Mongolia with Siberia just a little past that: That’s the journey from Shenzhen to Beijing. It’s 24 hours by train.

I buy my ticket the day beforehand. I show up at the counter with “Shenzhen: 18/7/2013; Beijing: 19/7/2013; Hard Seat” written on it in the best Mandarin characters I can manage. The attendant looks at it and answers back in clear English: “No hard seat left. Standing only.”

Well, this will be an experience. 24 hours across China, standing room only.

2PM, the next day, the train departs. Our car is packed. Most chairs have someone standing between them, and four of us are clustered at the back, by the locked door to the baggage car. There’s a bit of room here. Some folks have brought tiny fold-out chairs. I sit on my briefcase.

It’s not so bad. It’s not so good. It’s sociable. Having a westerner in the Hard Seat car draws smiles and no small bit of amazement. People want to talk. My Mandarin is still poor and only a few of them remember any English from their schooling. Every few minutes we wedge to the side to let the conductors get into their rest compartment, the luggage car, or the electrical room.

Where am I from? We wedge to the side to let a train worker into the electrical cabinet. What do I do? We wedge to the other side to let the conductor into his rest compartment. Why did Snowden do what he did? We wedge back against the side to let the conductor back out. How long am I in China? We wedge to the side to let a train worker check the luggage car behind us. Is Snowden still in Russia?

Things get a little gross as time passes. Spitting is acceptable in Chinese culture. People will just hawk one up, loud as they can, on the sidewalk. The back of the train holds the trash bag, which is the place to spit on the train. So people come back, hock, and spit, every few minutes. Meanwhile, we shift to the side to let another train worker past, this time to check the luggage car or twist another knob in the electrical cabinet, or take a 10 minute nap before they’re called back to duty again.

It could be worse. The end of the car is normally also the place where people go to smoke. Blessedly, smoking is shut down for car end. I don’t know why, but people are constantly coming back to our section with cigarettes and being turned back by the people around me. It’s hard enough being in the spitting section. Being in the smoking AND spitting section would be a bit much.

Three Days in Shenzhen

Three Days in Shenzhen

The sound of the room door opening wakes me; it’s a new hostel roommate. We get to talking (his English is better than my Mandarin) and quickly turn to, “What brings you to ShenZhen?”

“I come to see famous hackerspace,” he says.

At which, of course, I get giddily excited and explain that’s just what I came to ShenZhen to find.

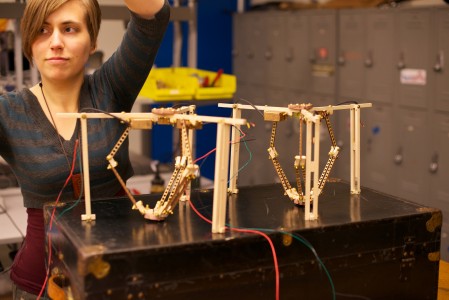

If you haven’t heard the word hackerspace before, here’s the deal: A hackerspace is a shared place for creators of software or whatever else, to get together, figure our problems together, and celebrate their creations. Hacking, to people who call themselves hackers, is exploring what new, beautiful things you can push a tool do. Whether it’s making laser-burnt art panels, 3d printing a mathematical equation into a real-world art object, or getting a piece of software to do something its creators never imagined, that’s all hacking.

So yeah, I went to meet with Chinese hackers. Not the kind that you hear about on the 6 O’clock news. The other kind.

It turns out, I’m crashing across the street from one of China’s most famous hackerspaces: Chaihuo Makespace. Actually, it’s ShenZhen’s ONLY hackerspace. I find this shocking, but each person I ask, incredulously, agrees: This is ShenZhen’s only semi-public space to swap hacks. The city is a solid brick of electronics manufacturing and related industries, and you can find more mills and lasers and circuit printers than anywhere else in the world, maybe. But it’s all in private hands. If you want to go someplace, borrow a 3D printer for a couple hours and just get down to some serious making, Chaihuo is it.

We play around during a demo of a new project from SeeedStudios: The “Grove” series of electronic building blocks. These are little circuit bits a child could plug together to make simple machines and concepts: lego for circuits. It fits somewhere between the “littleBits” line of toys, and getting kids to start plugging sensors and motors into an Arduino microcontroller and home brewing their own robot.

Afterwards we talk more. I learn that there are two start-ups operating out of Chaihuo (which is about the size of a studio apartment). Chaihuo is also frequented by the SeeedStudios crew, and Hao. Hao built DoraBot, a motorized wheelchair with a computer and a screen where the person would sit. It doesn’t click right then, but I’ve seen DoraBot back in San Francisco, in our hackerspace, “Noisebridge”.

Afterwards we talk more. I learn that there are two start-ups operating out of Chaihuo (which is about the size of a studio apartment). Chaihuo is also frequented by the SeeedStudios crew, and Hao. Hao built DoraBot, a motorized wheelchair with a computer and a screen where the person would sit. It doesn’t click right then, but I’ve seen DoraBot back in San Francisco, in our hackerspace, “Noisebridge”.

And of course, he’s already friends with Alex.

We also meet Kevin Lau, one of the founders of Seeed Studios. He invites us to come for a tour the next day. Naturally, we accept.

Seeed is pretty neat. We get the nickel tour, from the backdrop behind the greater’s desk made of old circuit boards, through R&D, down to the floor below for actual circuit building and “JaiYou!” contracts. “JaiYou!” is the local, untranslatable word of effort. It’s something you shout at athletes to encourage them to push harder. You might say it to a friend, as praise for accomplishments. And if you get a job that you want to knock out in a day to impress the client, that’s a “JiaYou” job. SeeedStudios has one floor for JiaYou.

The closest you can get to a literal translation of “JiaYou!” is “Step on the gas!” But JaiYou gets said for every kind of circumstance of encouragement. Those youtube time-lapse videos of Chinese skyscrapers going up in 15 days of round-the-clock work? A tribute to “JiaYou!” Effort, speed, and results for their own sake.

Another note that comes up in conversation with both Hao and Kevin is their awareness of China’s reputation for copying, not creation. “Shanzhai” is the word for it in Mandarin. “Shanzhai” is the culture of reverse engineering and copying. This could be an homage to the original. More often in the modern world, it’s to recreate the original with cheaper parts and sell it for less. They joke about ShanZhai. And they look down on it. They both want to be creators, not imitators.

Kevin points out how SeeedStudios’ circuitboards now have the inscription “Innovate with China” printed on them. “Like a response to Apple’s marking their products, ‘Designed in California, Made in China’ on the box?” Kevin nods.

After that, we head into HuaChiangBei. This is the legendary core of Shenzhen’s electronics industry. If Akihabara, in Tokyo, was the world hub of electronics in the ’80s and ’90s, HuaQiangBei in Shenzhen is the place today.

Take 3 city blocks wide, east to west, and 5 blocks tall, north to south, and pack it with multi-story malls. Set up each of these malls as an open floor, packed cheek-to-jowl with 5 by 5 stalls, each one holding one or two exhausted salespeople, and one kind of product. Each stall is packed in solid. Most don’t even make room for an entry gate: You slide a the blocks of the counter out of the way to get in or out. Customers stand in the aisles between stalls. At noon, half the merchants are head-down on their counters, taking a siesta from the monsoon heat, or slurping down a lunch of noodles.

Blessedly, no one’s going for the hard sell. The hundreds of merchants you pass are content to let you go on your way, knowing that you’ll stop with questions if you have any. No one has the energy to be a hawker in the swelling heat of the season. And their products are individually obscure: Why should any merchant expect you need a hundred or ten-thousand power switches? With each merchant’s laser-tight specialization, the benefit of flagging down random passers-by just isn’t there. When someone needs to pour over 30 different power switches to find the one that’s just right for them, they’ll come to you. The same goes for the guy with 50 different makes of button to your right, and the guy past him who has 20 different power rectifiers to choose from.

“TV Sticks” – these palm-sized cartridges plug stright into a TV’s HDMI port. Plug in a mouse and a keyboard and you’ve got a basic computer for 50$. It’s the same guts as your android cell phone, but using a computer’s I/O scheme.

Actually, this merchant isn’t selling full TV-Sticks. They’re selling a housing. The same way most of the other merchants in HuaQiangBei are selling just one component, this guy is selling generic housings, for anyone who wants to make one of these bargain-basement computers.

Shenzhen, you’re a place I need to see more of. But first I want some serious tourist time, to sit down with an iced coffee and an unfinished manuscript. Let’s head north, and take the slow train back, with lots of stops along the way.

Next up:

24 Hours to Beijing; Standing Room Only

Just In Time Trip Planning

Or: “I didn’t expect to be in that language this trip.”

Original Rough Plan: Run around China for a while, then do this trip:

Cheap flight from Beijing to Saigon, bus to Phnom Penh, riverboat to Siem Riep, bus & train to Bangkok, train to Krabi, then back to Bangkok and fly home.

I’ve wanted to do the overland trip through Cambodia. Also to get some rock climbing in at Thailand’s best limestone cliffs in the bargain.

The Hitch:

All the Saver Frequent Flyer trips from Bangkok to San Francisco are now filled until September.

Also full until September: Shenzhen to SFO, Shanghai to SFO, Beijing to SFO, and Singapore to SFO.

Tokyo’s available, though.

There’s a cheap flight from Hong Kong to Tokyo. That works. Now figuring out how to squeeze the most vacation out of the time in-between.

And this, friends, is the fun of plotting a one way trip and figuring it out as you go.

Next Entry:

The last 3 Days in Shenzhen: Makerspaces and the world’s largest electronics market.

How-To: Bypass the Great Firewall of China

- Perform these steps BEFORE going to China. Many of the sites you need to reach to bypass the Great Firewall are blocked by the Great Firewall.

- Too late? Find someone in China who’s already punched through the Great Firewall to help you.

- Set up GoAgent on your browser and a Google App Engine account according to the instructions here.

- Those instructions are for FireFox. I was shown how to get it running under Chrome, by a Linux fan, and between the two of us we had an easy time interpreting that for my mac.

- I launch the proxy agent manually, by going into the <GoAgent>/local folder and running “sudo python proxy.py” there.

- When I say “<GoAgent>”, I mean the folder you unzipped from your download of GoAgent from code.google.

- The SwitchySharp Chrome extension gets installed in Chrome by going to Settings->Extensions within Chrome, and then dragging the (only) .crx file from <GoAgent>/local into the Chrome window that shows your current extensions.

- You probably want to update its autoproxy rules from the live servers:

- Click the SwitchySmart Chrome Extension icon that’s now in the upper-right of your Chrome window.

- Click “Options” under its menu. A new tab appears.

- That tab has a tab-bar of its own. Click “Switch Rules” there.

- At the bottom of that window, click the button to “Update List Now”

- Your computer won’t be happy loading sites, still: routing everything though a proxy makes it look like you’re being snooped by a man-in-the-middle hacking attack. You have to add the proxy’s certificate to your trusted certificates list.

- On Mac, open the program “KeyChain Access”.

- Drag the certificate file from <GoAgent>/local into an unlocked keychain there.

- You should see a new certificate for “GoAgent CA”. You might have to search to narrow down to see it among the hundreds of other certificates a mature computer will have in its keychain.

About

Welcome to WhereAmI.org, Sam Brown’s scrapbook on the interwebs.

Right now I’m pulling this site out of mothballs, because:

- I’m traveling again. WhereAmI started off as a travel blog. Rather, a ‘homepage’. That’s what we called pages like this back when we had to uploaded files with command line FTP, uphill both ways, through the snow.

- I can’t get to the usual social networks, since I’m running around China at present, and the Great Firewall blocks social networks like FacePlus, InstaTwit, and the rest. So you’re not going to see me in the usual places for a while. If you’d like to keep up, stop in here.

Oh, and you know you get sick of people’s personal sites saying that they’re “Under Construction” no matter how long they’ve been up? Well, I just coughed up this iteration of WhereAmI at 5AM, July 14th, 2013. So for now, it looks pretty darn good. And yes, if you’re back in the US and reading this as soon as I post it, I AM POSTING FROM TOMORROW. So you can deal with the site being a little hinky. And by “deal with” I mean “tell me about it in the comments and I’ll fix it.”

Oh, and you know you get sick of people’s personal sites saying that they’re “Under Construction” no matter how long they’ve been up? Well, I just coughed up this iteration of WhereAmI at 5AM, July 14th, 2013. So for now, it looks pretty darn good. And yes, if you’re back in the US and reading this as soon as I post it, I AM POSTING FROM TOMORROW. So you can deal with the site being a little hinky. And by “deal with” I mean “tell me about it in the comments and I’ll fix it.”

Shenzhen: First Impressions

Mike Daisy Was Full of It.

A few months back, Mike Daisy got himself an entire segment speaking on This American Life. He talked about Shenzhen as “the place where your crap comes from”; A city of concrete and neon that “looks like Blade Runner threw up on itself”. In Mike’s dystopian Shenzhen, the sky is a poisonous mercury silver, and bowels of a sprawling highway system punch through the city only to end abruptly in a traffic cone that hangs over a 30 meter drop. Everything is bustling, toxic, and under construction.

I haven’t found that Shenzhen yet. Here’s the view from my hostel, where I’m writing this:

There’s one especially touching segment in Mike’s story where he meets with disabled victims of Chinese industrialization: Men who have been polishing the screens at the iPad factory, who now live with tremors. Their hands are curled up, shaking wrecks after years of handling nerve-poisonous n-hexane screen cleaners without protection. He hands his own iPad to one of them, who touches the screen in awe and says (through his translator) “it’s a kind of magic”. He’s given up his life to make iPads, this man from Mike Daisy’s story, but he’s never even seen one turned on.

Funny how just as many folks on my train ride in from the airport were tapping away on their touchscreen phones and phablets as in Silicon Valley.

Speaking of train rides, let me admit a prejudice: I am inclined to count a culture’s ranks in civilization in part by how clean and generous their public transit is. Are their trains to everywhere you want to go? Do they come often? Is it affordable to everyone alike?

This is an especially techy tidbit: The subway tokens have something like an RFID or NFC tag embedded, so even through they’re one-ride-only, you tag them in to open the entry gate the same as you would a rail card. Then when you drop them in the exit gate from the subway system, it knows if you paid enough for the length of your ride.

By this metric, Shenzhen is second only to Barcelona in civility. The trains come every few minutes. The network is vast, getting you within 10 minutes of anywhere you want to be in town. A medium-haul train ride will set you back 4C¥: About 60 cents at the current exchange rate. Above each train door is map of the line with LEDs showing where you are now, which direction you’re headed, and whether the doors on the right or left side of the train are set to open at the next stop, making using the system idiot-proof.

The Great Firewall? You Can’t Miss It.

It’s not all wine and roses. Chinese censorship? You’re going to hit it the first time you log onto the ‘net. Facebook, Google Plus, Twitter; navigate to any social network and you’ll run into…

Google what’s up with that, click any link and you’ll run into…

Other web sites (like this one) seem to run just fine. Still others are in a grey zone, loading slowly, frequently failing or dropping for minutes at a time. GMail and GChat occupy this limbo of sites that are available in China, but painful enough to use that Pavlov may suggest you prefer an alternative.

Actually, I’m pretty sure it’s not the hostel’s wifi. I’m uploading these (large) picture files and getting them back just fine.

Off to Find “My People”

I’ve been in China now for ~24 hours now, but I’ve just got my feet: Overnight in Beijing International Airport after my first connection to Shenzhen was cancelled, wandering across Shenzhen to a new hostel after the first one I’d reserved a room at had given it away when I didn’t show, sleeping until a few hours before dawn to catch up, pulling WhereAmI.org out of mothballs and then writing this blog post.

Time to find my feet for real: To find the local Makers, techies, coffeehouse addicts, and the rest. Also, I need to get my own phone turned on to this network, lest I shatter every notion that the locals have of Americans as being affluent movers and shakers. Because clearly, to the people around me, anyone who isn’t tied to the ‘net at will is at best a primitive cretin.